The shades of night were falling fast,

As through an Alpine Village passed

A youth who bore that snow and ice,

A banner with a strange device,

Excelsior!

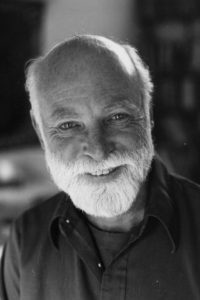

Douglass J. Wilde, Professor of Engineering Design at Stanford University, was known to many of us for his scientific and engineering contributions, and for his simple and caring attitude towards everyone who encountered him — ‘Doug’ to us all. Doug’s apparent simplicity hid a complexity of which we get a glimpse from the quotes he used in introducing each chapter in his many books, like the one above by H. W. Longfellow in his first book Optimum Seeking Methods (1964).

Doug was born in Chicago, August 1, 1929 and was educated at Carnegie Institute of Technology (‘Carnegie Tech’ before it became Carnegie Mellon University) earning a BS in Chemical Engineering (1948); at the University of Washington earning an MS in Chemical Engineering (1956) with a thesis on Aggregate Fluidization of Solids by a Liquid; and at the University of California-Berkeley earning a PhD in Chemical Engineering (1960) with a dissertation on Central Control of Processing Systems and Andreas Acrivos as his research advisor. Between his studies he worked as an engineer at the Pittsburgh Coke and Chemical Company in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and the Union Oil Company of California in Rodeo, California. He started his academic career as instructor and assistant professor at UC-Berkeley’s Chemical Engineering followed by a year as a Fulbright Exchange Professor at École Nationale Supérieure des Industries Chimiques, Nancy, France. After short stints at the University of Texas Chemical Engineering and Yale University Electrical Engineering, he joined Stanford University in 1963 as Associate Professor in Chemical Engineering becoming a full professor in 1973. That same year he left Chemical Engineering and joined the Design Division in the Department of Mechanical Engineering with the unique title of Professor of Engineering Design, where he remained until his retirement.

Doug’s research work on optimization had an interdisciplinary flavor from early on. As a trained chemical engineer, he approached a mathematical subject like optimization from a practical perspective but without sacrificing rigor, yet not letting rigor make the thinking opaque and over esoteric. He had always been preoccupied with how apparently good methods can give you wrong results. In his first Optimum Seeking Methods book his “… analysis of interactions between variables shows how one may blunder into a false optimum.” In his second book, Foundations of Optimization (1967) with Charles Beightler, inspired by Voltaire’s critique of Leibnitz’s optimism in Candide, Doug goes on to say “There is, moreover, a tendency towards uncontrolled enthusiasm which leads to exaggerated claims about what particular optimization techniques can do. This, together with the use of incorrect proofs to demonstrate incorrect results, could bring upon optimization theory the same undeserved disrepute that Voltaire hung on Leibniz’s philosophical optimism.” In our co-authored book Principles of Optimal Design: Modeling and Computation (1988), the emphasis had shifted further to the modeling side of an optimization problem: “In modeling an optimization problem, the easiest and most common mistake is to leave something out… As a perhaps unexpected bonus, often such preliminary (modeling) study leads to a simpler and thus more clearly understandable model…”

While Doug did not initially frame optimization as a design process, he was keenly aware of its obvious interest in “… the practical world of production, trade, and politics…” By the early 1970s he had come into thinking of design as a decision-making process and thus opening it to the world of optimization. The book Optimization and Design (1973) Doug co-edited with his students Mordecai Avriel and Marchel Rijckaert was a now-classic collection of ideas in this thinking evolution assembled from the Summer School on the Impact of Optimization Theory on Technological Design in Leuven, Belgium — summer schools being a most lovely of European research traditions. By the time I met him at Stanford in 1974, he had combined his interest in design with his dubiocity of the extant numerical optimization methods, culminating in his Globally Optimal Design (1978) monograph — straight out of his lecture notes in the classes I had attended. I recall going to his office for a research meeting clutching my detailed notes on the back side of used computer printout paper (the large one with perforated edges). After talking to him for a while, I realized he was not listening, and his eyes had glazed. And so, I asked him what’s wrong —to which he replied, “I told you I don’t want to see any more d… computer outputs!” After I explained that I was only using it as scratch paper and pledged that I would never compute anything, he brightened up and urged me to start over, happy as a clam.

In the 1980s, Doug’s mathematical bend and fascination with geometry led him also to research work on mathematical geometry and the emerging research fields of computer-aided design and computational geometry —evidence that his thinking was less rigid than one might surmise from the above story.

Doug really cared about people. He was visiting me in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1985 when I told him I was assembling my class notes for a Cambridge University Press textbook that would show the intimacy between modeling and solving optimal design problems. Doug said, “Sounds like a fantastic idea, can I be your second author?” Of course, I agreed and both of us went on sabbaticals in 1986 with a plan for what would be our individual parts. The next year we assembled our chapters and sent them to the publisher. The answer came back quickly that the manuscript was twice as long as we had agreed and had to be cut in half. Doug and I agreed we needed to talk in person, and I travelled to Stanford staying at Doug’s house. After two days of discussions, we ended the second night agreeing that we were going to write two books, and went to bed. At breakfast the next morning, Doug started by saying “You know I think I can cut chapters x, x, and x.” And I immediately replied, “Yea, I was thinking that we don’t need chapters y, y, and y). Three months later the manuscript was with the copy editor.

In a more official capacity, Doug was probably the first academic administration officer to address the plight of minorities serving as director of the Stanford Mathematics and Engineering Science Achievement Center and as associate dean in the School of Engineering, partly a result of his adamant student advocacy. After he retired, his caring for people led him to study how design teams are formed and operate successfully. His studies on C. G. Jung’s cognition theory and experiences with the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator psychological instrument were collected in his book Teamology: The Construction and Organization of Effective Teams (2009).

Doug’s flair was always evident in his interactions with colleagues, young and old. For a while he was even part of a Shakespearean troupe in San Francisco. One can imagine his rendition of King Lear! But contrary to the old king, Doug was always approachable, always ready with an encouraging word, always treating everyone with care and respect. Doug passed away quietly at his home on October 28, 2021. We will all remember him fondly for his intellect and for his humanity.

Panos Y. Papalambros

University of Michigan

Photo Courtesy of Stanford News Service

J. Mech. Des. June 2022, 144(6): 060101, https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4054271